Every writer knows the terror of the blank page.

You can have a whole cast of fully fleshed-out characters, a vivid setting, and an awesome idea. But what do you do after you type “Chapter 1”?

If your stories always lose focus once you start working on them, you might need to do some planning first.

A plot diagram keeps you from getting lost while you tell your story. It’s like a map you can follow on your expedition through the lands of creativity.

In this article, we’re going to learn exactly what a plot diagram is and how to make one.

Get creative and sign up for Miro today!

What is a plot diagram?

A plot diagram is a visual representation of a story. Just by looking at it (assuming it’s labeled properly), you should have an idea of what the complete product will look like.

To explain exactly how it works, we’ll need to define a few key terms.

It’s hard to get any two writers to agree on the exact difference between plot and story, but there’s a very general consensus: the story is what happens, and the plot is how it happens.

English novelist E.M. Forster famously said that “The King died, then the Queen died,” is a story, but “The King died, then the Queen died of grief” is a plot. The story outlines the situation and proposes a sequence of events; the plot is concerned with cause and effect.

Stories can be hard to diagram. They’re often based on feelings and images as much as concrete ideas. But unless your work is extremely experimental (which puts it outside the scope of this article), plots have to flow in a continuous line. That makes them easy to diagram — and if you can’t diagram your plot, it needs some work.

We also need to define action. It doesn’t necessarily refer to fight scenes or car chases but to your plot’s degree of complication and tension.

You can consider the plot diagram to be a graph with time as the x-axis and action as the y-axis. As your story nears a climax, the action should rise and rise, only falling at the very end.

There are many kinds of plot diagrams, but they all share a few traits:

- An opening

- Rising action

- A climax

- A resolution

Those terms come from the best-known plot structure and the one we’ll start working with today: Freytag’s Pyramid.

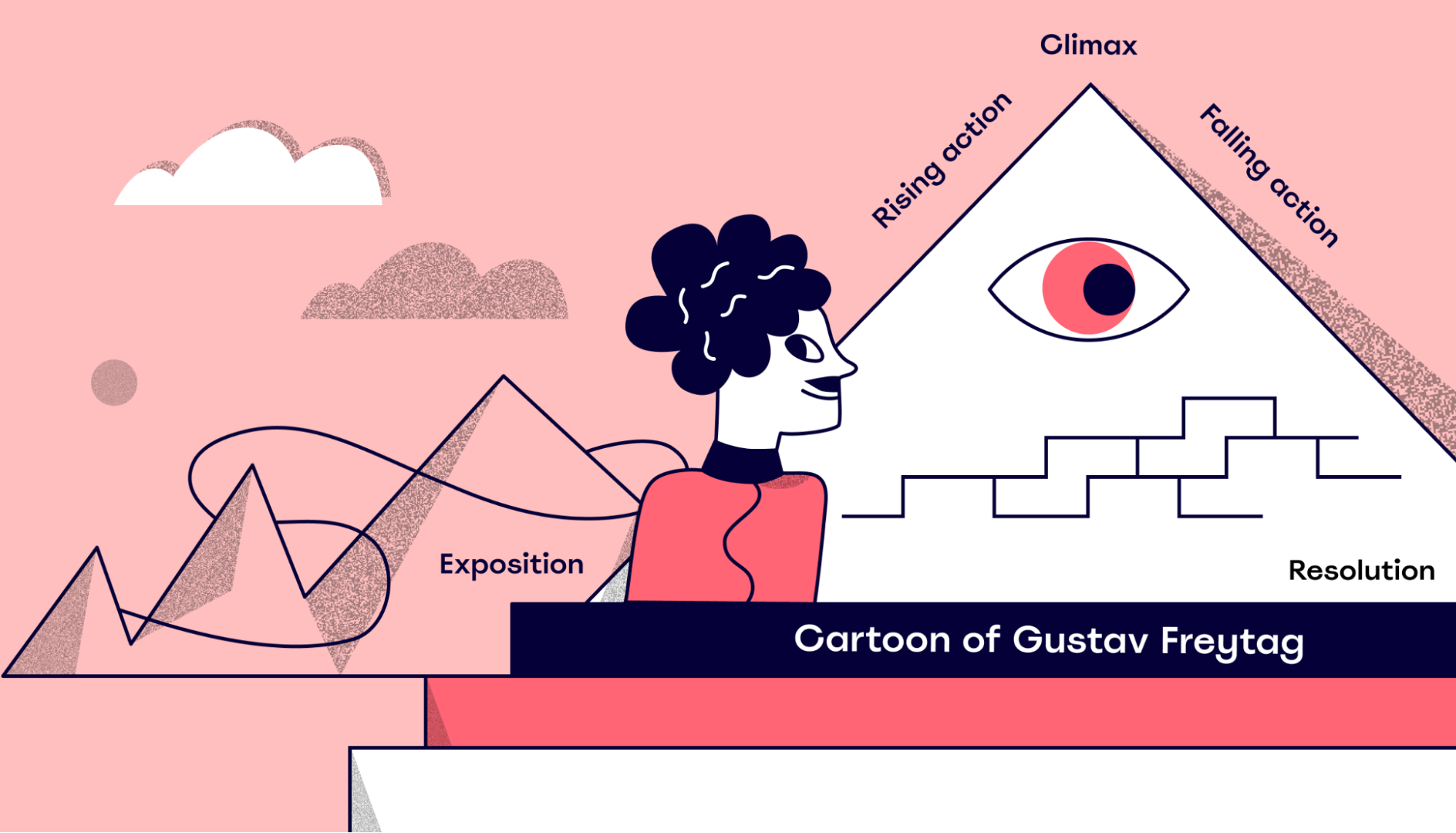

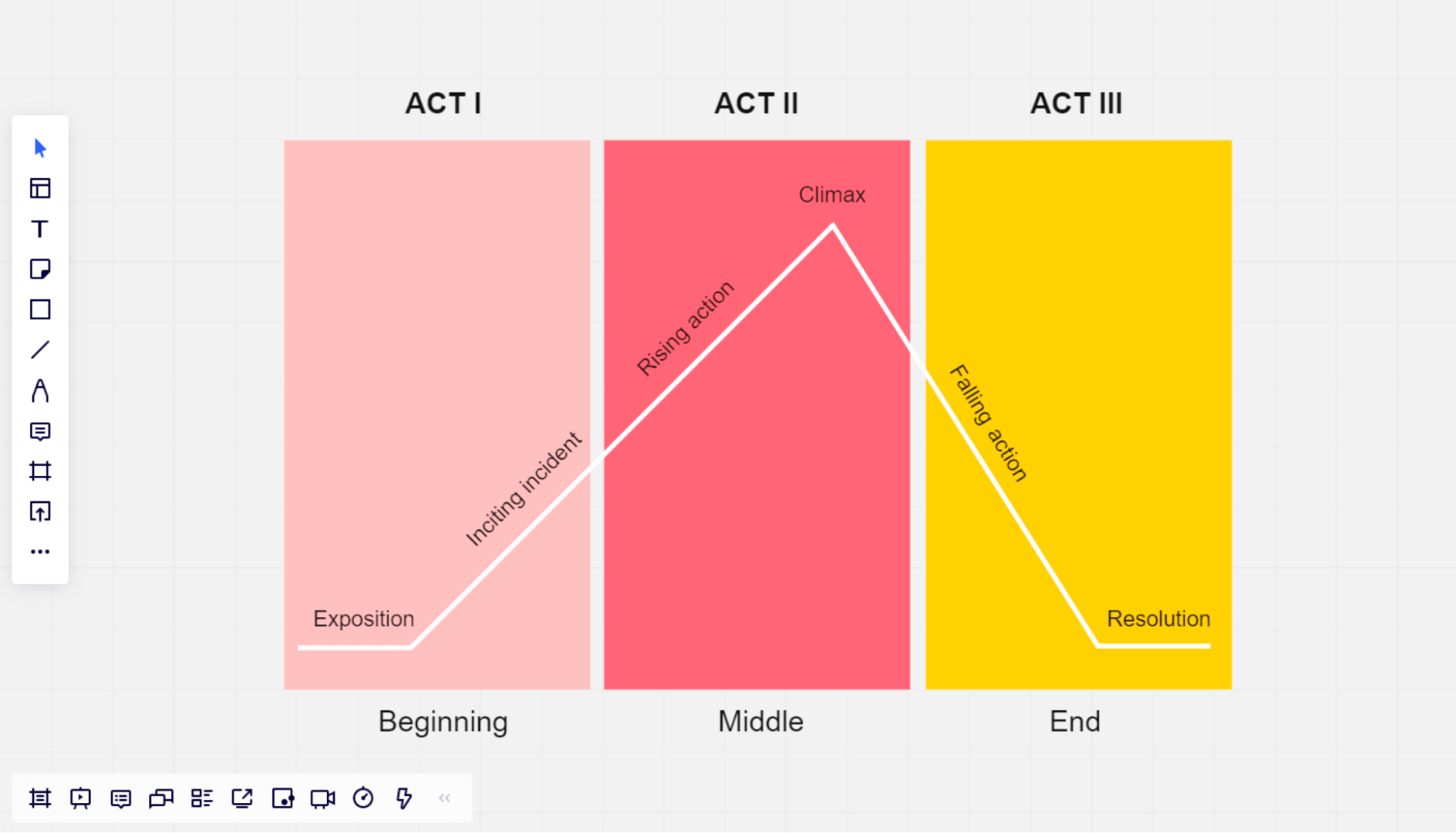

Freytag’s Pyramid was developed by Gustav Freytag, a German playwright. Freytag modeled plots as a series of steps held together by a line that rises, hits a peak, and then falls. If you’ve been through a fifth-grade English language arts (ELA) class in the age of Common Core standards, you’ve seen this already.

The plot beats along Freytag’s Pyramid are:

1. Exposition: The setting and characters are introduced. The audience is given the information they’ll need to understand the conflict.

2. Inciting incident: An event occurs that makes the conflict inevitable. For example, this could be the moment that the protagonist and antagonist realize they can’t both achieve their goals.

3. Rising action: This is almost always the longest part of the plot. In the rising action, events occur to raise the stakes and complicate the characters’ attempts to fulfill their objectives. However, not every scene in the rising action relates directly to the main conflict. You can also use this time to develop the characters, set up and resolve subplots, examine the themes of your story, and foreshadow future events.

4. Climax: The climax is the moment in the plot where the tension is highest. At the climax, the central conflict must resolve, though not necessarily in favor of the protagonist. Once the climax has passed, it should be impossible to go back to the way things were — and if it’s not, that wasn’t your climax. Character arcs, subplots, and thematic questions can resolve along with the main conflict.

5. Falling Action: What happens to the characters and the world after the climax? Obviously, everything doesn’t just stop when the conflict resolves. Your characters will need to find their way to a new status quo, ideally in a way that provides the reader with a sense of closure. The falling action is normally much shorter than the rising action, but its length varies based on the story being told.

6. Resolution: Also called the denouement, the action in the resolution ties up loose ends and gets the story to a place where the reader is comfortable leaving it. Your resolution is aesthetically critical since it’s what the reader will remember afterward.

There are plenty of ways to diagram a plot other than Freytag’s Pyramid. We’ll go over some of them in the “types of plot diagrams” section. But before that, let’s address why a writer should bother with any of this.

Why use a plot diagram to write stories?

As a creative writer, you might find the idea of diagramming your plot to be overly restrictive, like the dull “poetry graph” the students tear up in Dead Poets Society. But it doesn’t have to be.

A plot diagram is just a graphic organizer for your thoughts. It has two main purposes: to keep yourself focused while writing the story and ensure you’re creating the kind of story people want to read.

Focus is the main factor separating writers who finish their stories from writers who don’t. Whenever you feel unsure where to go next, having a plot diagram to reference can make the difference between finishing your creative writing project or abandoning it.

Furthermore, assuming it matters to you that your story is published or widely read, you need to be aware of the general plot structures people are looking for. A plot diagram helps you conform to the rules enough to capture a reader’s attention, but having an established baseline also gives you more freedom to experiment.

You can also use a plot diagram to help you understand other people’s stories. Whether you’re an ELA student looking for a new perspective on a classic or just want to be able to say something interesting at your next book club meeting, you don’t have to be a writer to get value out of a plot diagram.

How do you create a plot diagram?

Before you do anything, brainstorm your ideas. We know the creative process can vary from person to person, so take your pick when selecting the best way to do it. After you have decided the direction you want your story to go, follow the steps below to create your plot diagram:

1. Decide on your story idea

Remember what E.M. Forster taught us: your plot is just a means of telling your story in a way that keeps your audience invested. You can’t come up with a plot without a story any more than you can draw blueprints before you know whether you’re building a school or a hospital.

Unfortunately, this is the one part a plot diagram can’t help you with. The good news is that coming up with an idea is the fun part. All you need is to let your imagination run wild until you associate some concepts together in a new, exciting way. Mind map templates can be helpful here.

Now is also the time to decide whether you’re writing a short story, novel, screenplay, or something in between.

And remember, it’s OK if the story changes while you write.

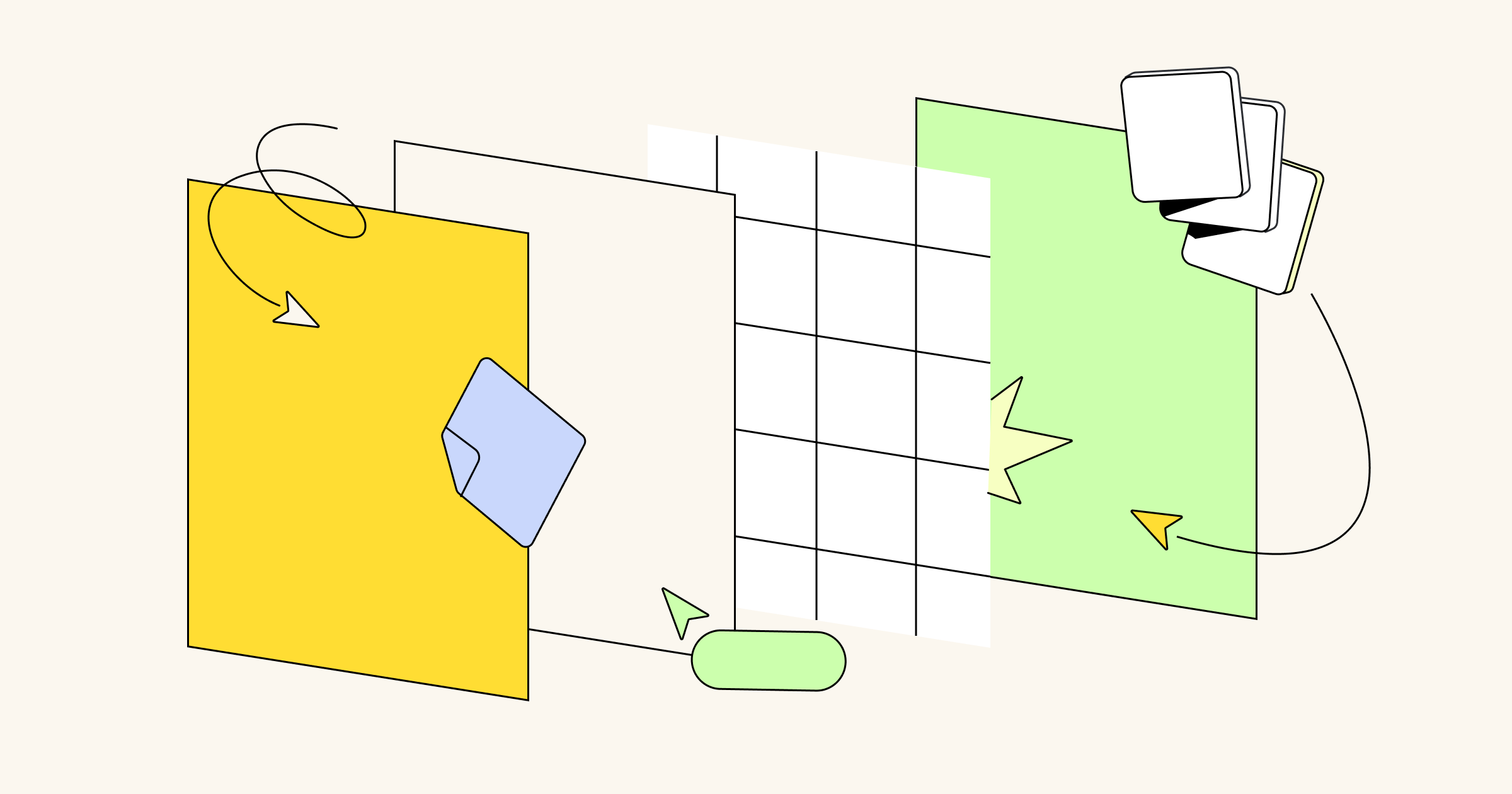

2. Start a worksheet, and draw the plotline

We’re assuming you’re using the Freytag Pyramid, but these directions will work for most plot structures.

Start by drawing a short horizontal line. Connect its end to another line that angles upward until it reaches a peak. Then add a third line that slopes down at a steeper angle and another short horizontal line.

It should come out looking something like this:

Tinker with it until it fits your thought processes. For example, if you’re using a Hero’s Journey model, you might prefer circles instead of sharp lines. Find out what works for you — the important thing is the rise and fall.

3. Label the plot beats

Next, add the following labels:

- Exposition: The horizontal line at the start, representing the status quo.

- Inciting incident: The intersection of the first two lines, representing the moment tension and complication start to rise.

- Rising action: The second, upward-sloping line, representing the steadily increasing stakes of the conflict.

- Climax: The intersection of the second and third lines, representing the irreversible resolution of the conflict where the action starts to fall.

- Falling action: The third line, representing the story’s progress toward resolution.

- Resolution: The final horizontal line.

Your diagram should look like this:

Each line should be long enough to accommodate notes and smaller labels that describe events in the story. In particular, make sure you leave enough space on the rising action line, around the exposition line, and above or below the climax point.

4. Add the story events you know

It’s time to get into the really fun part: using the curve you’ve drawn to plan out your story. Take each part of the story you already know from your original idea, and plot it along the arc.

It’s OK if your concept has some holes in it — this is all about helping you reach a complete idea. You might find that just looking at a few plot points written along the curve will give you some notions of how they might tie together.

5. Fill in the gaps

The most important thing in a plot is consistency. Even if your story is about unicorns fighting vampires on the rings of Saturn, there must be a believable reason why Unicorn Commander Glitterhoof decides to risk her life attacking the vampire fortress.

(That said, your characters don’t always need to make good decisions. Actions that make perfect sense can still turn out terribly).

Fill in any holes in your plot arc until it’s consistent along the diagram. When you can tell your story from start to finish using only the conjunctions so and but (not only and), you’re ready to move on.

6. Add other details

Even a complete plot is only the beginning of a plan to tell a story.

Add information to the plot diagram that helps you understand and remember concepts like:

- Protagonist: The main character the reader follows through the story. Every protagonist needs a clear goal.

- Antagonist: A character who stands in the protagonist’s way and prevents them from getting what they want.

- Setting: The time and place where your story unfolds.

- Conflict: The reason the story is happening at all — because two or more mutually exclusive outcomes are trying to assert themselves at the same time.

- Subplots: Smaller-scale plots that unfold along with the main plot. Subplots commonly concern character development or the relationship between two characters.

- Themes: Any statements made by your story that resonate meaningfully beyond it. “Man should not play God” is a theme; “snow goons are bad news” is not. Themes are rarely stated outright but alluded to by the events that make up the plot.

As you label details, take care to keep your plot diagram from getting so visually cluttered that it’s useless. If you have so much information that it’s filling up all the white space, it’s time to start writing the story.

7. Start writing

There’s no choir of angels when your plot outline is finished. When you feel ready to start writing, you’re ready. Neither your plot nor your writing itself is set in stone. They can change and influence each other as you work.

Types of plot diagrams

Is the Freytag Pyramid not firing up your imagination? Try one of these seven other popular plot structures.

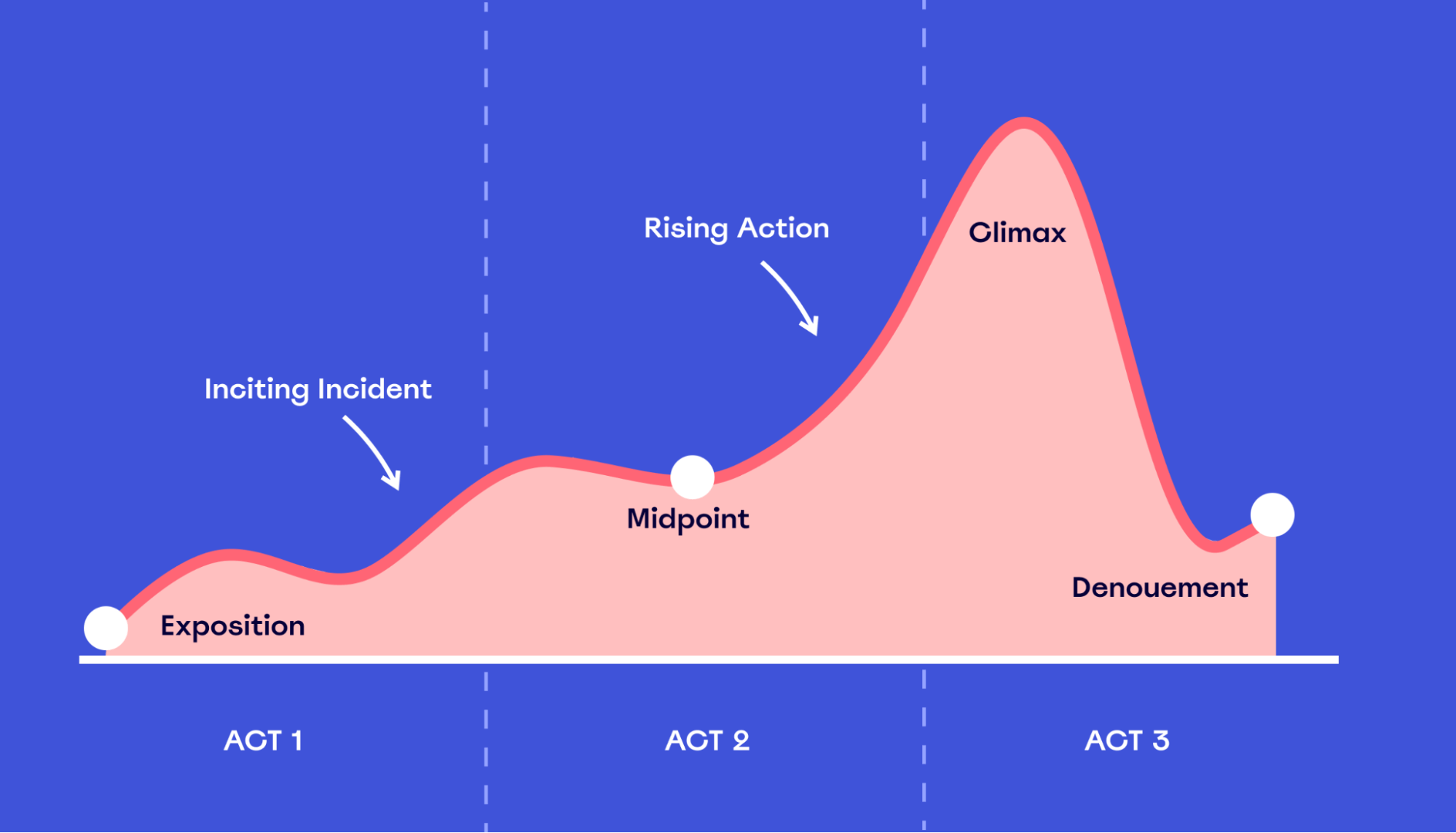

1. Three-act structure

The most basic structure for a plot is a beginning, a middle, and an end. A three-act structure takes that principle and grafts it onto a linear plot diagram.

It replaces the pyramid with three smaller peaks, each followed by a valley. The first peak is the inciting incident, the second peak is a “midpoint” event that raises the stakes, and the third peak is the climax.

2. Five-act structure

Freytag had a five-act structure on his mind when he developed his pyramid. Popularized by the editors of Shakespeare’s plays (though Shakespeare himself didn’t use scene and act breaks), the five-act structure was later adopted by broadcast TV to write hour-long episodes with four commercial breaks.

The five acts are as follows (note placement of the climax):

- Introduction: The exposition and inciting incident (Hamlet learns that his father was murdered).

- Rising movement: The story moves toward a turning point (Hamlet isn’t sure who to trust and fakes insanity to buy time).

- Climax: A turning point occurs that reverses the characters’ fortunes (Hamlet uses the play to prove Claudius is the killer but then kills Polonius).

- Falling action: Everything continues moving toward a payoff and/or unraveling toward catastrophe (Hamlet is banished to England but returns).

- Catastrophe: All the plot threads come together and pay off (Hamlet kills his uncle and dies).

Freytag originally established these beats to write tragedies, but they’re more versatile than they seem. Think about how everything going right for your protagonist can cause massive complications.

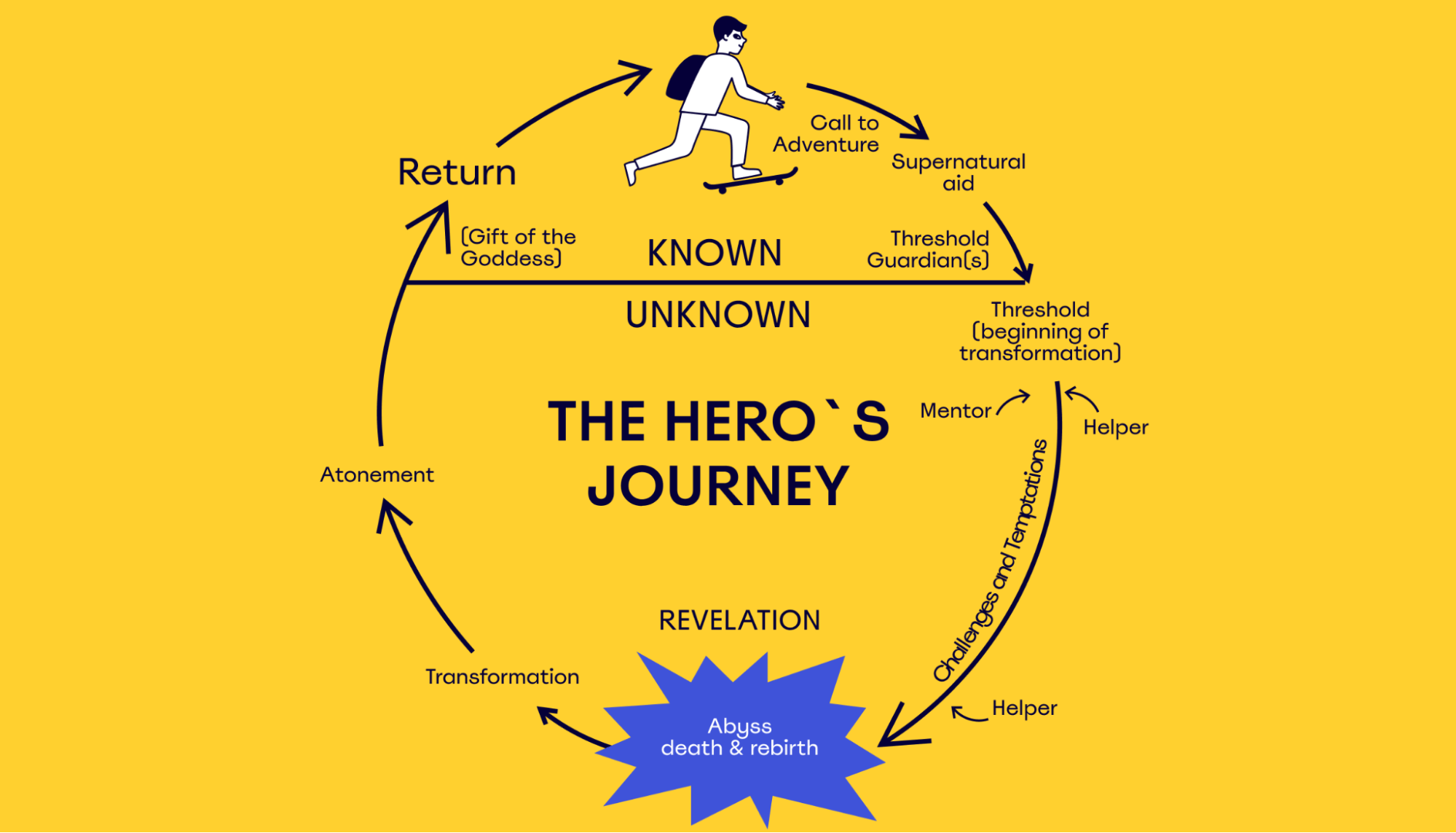

3. The Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell developed his famous “monomyth” as a theory of anthropology, demonstrating how different human cultures tell similar stories. It gained fame as a story structure when George Lucas used it to write the original Star Wars trilogy.

The Hero’s Journey is usually depicted as a circular path that takes the protagonist from the known world through an unknown world and back to the known.

Important elements of plot include:

- The Call to Adventure: The hero is given a reason to leave the known world.

- The Threshold: He crosses a literal or figurative point of no return.

- The Road of Trials: He faces several obstacles, including enemies, temptations to abandon his quest, and the need to atone for his own sins.

- The Return: He ultimately returns with a “boon” that changes life in the known world for good.

Dan Harmon adapted the Hero’s Journey into a story circle he uses to plot episodes of Rick & Morty. It can be expressed in a broken-up sentence: “The hero is in a place of comfort…but they want something…they enter an unfamiliar situation…adapt to it…get what they wanted…for a heavy price…then return to their zone of comfort…having changed.”

4. Fichtean Curve

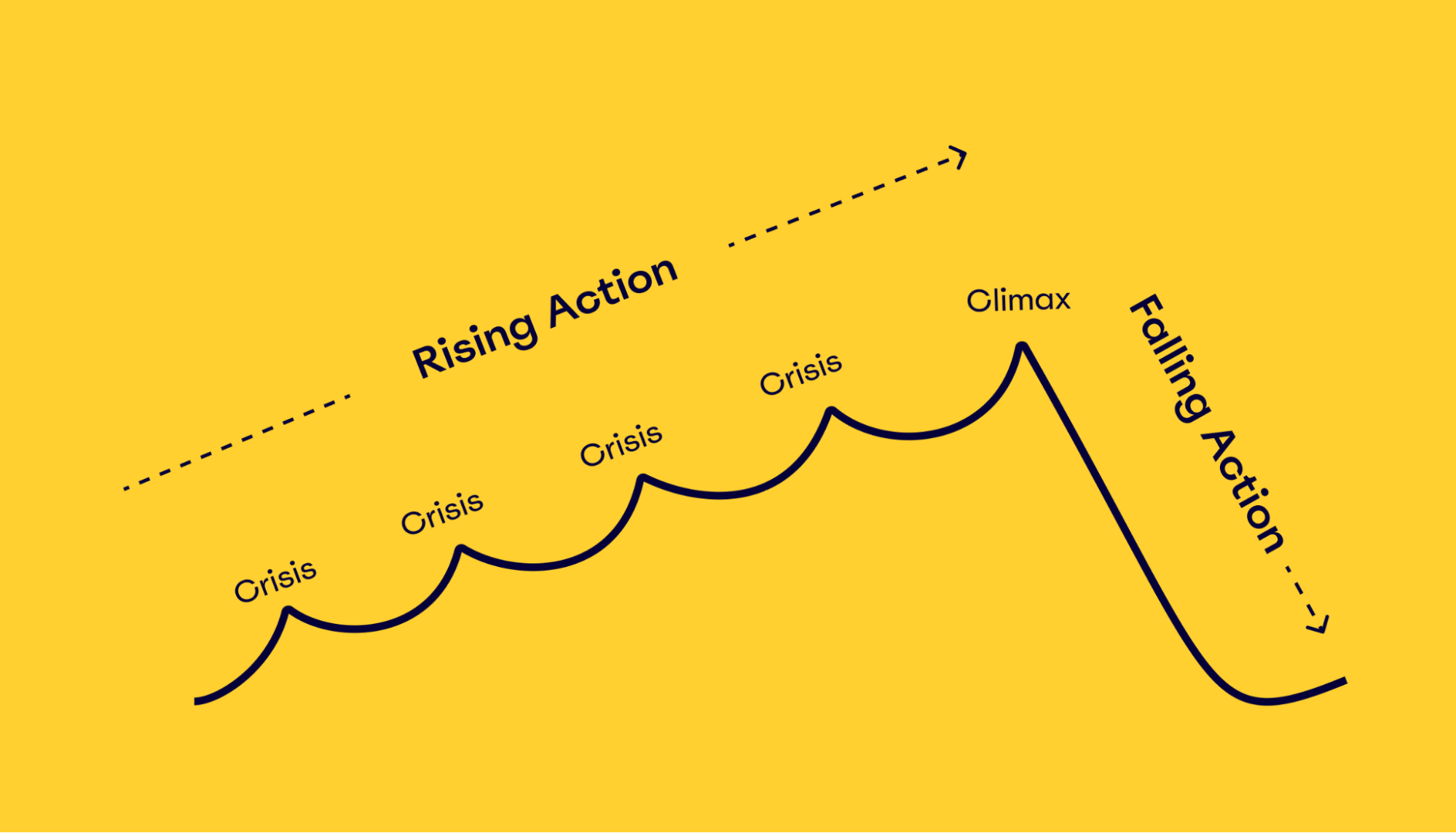

The Fichtean Curve is an alternative plot structure that looks a bit like a fish’s fin or Bart Simpson’s head.

It’s a simple but effective system: start with the inciting incident, then add an escalating series of crises until the climax. The Fichtean Curve is helpful when writing fast-paced stories, like murder mysteries or espionage thrillers.

5. Non-linear plots

Not all plots have to develop along a single line. You can tell stories outside of linear time, explore the same event from multiple perspectives, or write a “slice of life” story with no serious conflict.

Admittedly, these are harder to graph on a plot diagram, but it can be done. Start with a blank whiteboard, and let your creativity run wild. You might just find something that works.

Tell your story with Miro

Miro’s whiteboards are an easy way to draw a clear, helpful plot diagram and share it with others. We can’t tell your story for you, but we can make it a lot easier to keep your literary elements organized.