Ash Maurya is the acclaimed author of Running Lean and Scaling Lean. In 2009, a significant realization about the importance of developing products to meet real needs led him to the Lean Startup movement, which was pioneered by Eric Ries and Steve Blank. From there, Ash created several business modeling tools, including the Lean Canvas, Traction Roadmap, and Customer Forces Canvas. Today, his frameworks and methodologies are used by over a million people globally through his company, LEANSTACK.

I’ve been a fan of Ash’s for 15 years, and recently had the opportunity to catch up with him to discuss innovation, namely why it’s important to validate ideas quickly; how to focus on problems, not solutions; not just be a little better than the status quo; use metrics to track traction; and be cognizant of the Innovator’s Gift.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In a recent talk, you brought up the concept of “good enough.” What does that mean in a corporate context?

Starting is probably the most important thing that we can do with any idea. Get started, then discover insights along the way and course-correct. When you’re moving really fast and with a lot of uncertainty, it’s impossible to create a perfect plan because we don’t know what we don’t know. No matter how much research we do, some ideas don’t end up where we thought they would at the start. That’s why sometimes I say that a plan doesn’t need to be perfect. It needs to just be good enough to get to market where you can really learn something.

The lean startup is synonymous with “get out of the building.” What should you be doing before you get out of the building?

I usually recommend that people don’t rush outside the building. Yes, all the answers are eventually going to come from the market, but there is still quite a bit of planning and stress-testing work that needs to be done before we get out. So if we were civil engineers tasked with building a bridge, we wouldn’t take the plans and rush to go build a bridge and see what happens. We’d stress-test the bridge. We might use simulations, build models, load it up with 50 cars, and if the simulation fails, if the bridge collapses in our models, we would fix the model first.

That gives us inputs that we can then go validate. If I know, for instance, that I’m trying to build a $100 million business, and I need to get a customer paying me $10,000 a year, I’m looking for a $10,000-a-year problem. That gives me inputs that I can use in my validation versus just going out and getting lost in all the noise. There are going to be lots of problems. We can get outside and find lots of problems, but the key is finding problems worth solving.

What are the principles behind lowering the friction to ideation?

Unfortunately, the way we work today is we ask certain people to talk to the customers and gather business requirements. Then there’s the Elephant Whisper game where by the time it gets to the people doing the work, it gets mangled, so what we end up building isn’t what the customer wants. One of the mantras in Lean is bringing the voice of the customer closer to the people doing the work.

The idea of lowering ideation friction is a recognition that good ideas can come from anywhere. We want a diversity of ideas because the next big one could emanate from a customer service rep, a designer, or from an engineer, not just the business folks. We want to collect all these ideas and then double down on the ones that are really going to make our business model work.

How can tools like the Lean Canvas help address cumbersome proposal processes that prioritize completed templates over good ideas?

With a lot of the Lean models, those ideas are very raw assumptions that we can start to score and ask “What evidence do we have?”. With that kind of inquisition, we can get to a confidence level that allows us to fund those early-stage ideas versus just focusing on the overpolished version of that story.

Where does the myth of luck concept play in the process of bringing ideas to fruition?

I think of it as timing. People have studied that timing is a big factor for ideas. But it’s very hard to time an idea because it’s hard to predict the future. For those reasons, I like to think of luck and timing from a different perspective, which is not to ask, “Is this the right time to start something?” I suggest that you just get started and then test with evidence whether this idea could get lucky in the next six months, and the evidence should come pretty quickly.

How does the innovator’s bias relate to the myth of luck?

Innovator bias is a human condition that takes us back to how people are not comfortable with problems. We’d rather gravitate toward solutions. And with innovators, with entrepreneurs, that is a very strong inkling. When we see a problem out in the world, even if it’s a real problem, we very quickly start imagining a solution. We spend every waking moment trying to bring the solution to life. But when you’ve decided you want to build a hammer, everything starts looking like a nail. That’s the innovator bias, and it happens unconsciously.

Daniel Kahneman, a great psychologist who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, says that the smarter we are, the easier it is for us to get biased. In the product sense: The more we love product, the easier it is to get enamored with solutions, and unconsciously we start making justifications for the solution, or the hammer, we want to build.

What is the “Innovator’s Gift” in the Leaner Canvas template you created for Miroverse?

When we are trying to pitch an idea, it is very tempting to say, “I want to build this because,” and then rattle out a bunch of problems. A better way to think about this is not what we can do with a solution, but why we should build a solution. So the idea of the Innovator’s Gift is asking a different question, which is “What’s broken with the current status quo?” What’s broken with the existing alternatives that people are using?

AI is a great example. I run into lots of startups that are doing an AI thing, and they always rattle the benefits of AI. And I say, “Well, tell me what people do today.” So if it’s for copywriting and marketing, “what tools are they using and why is that broken?” And if we can latch onto problems there, then we can start talking about what could be better.

If an idea is worth solving, does there need to already be an existing alternative?

That’s a good thought experiment. I ask in my workshops, “Can you name a disruptive product at any time in history that didn’t have an existing alternative or competition?” The answer is no because there’s always an older way. It may not be a very optimal way, but there’s always an older way.

Is having an existing alternative that has lots of problems enough for an idea to be good?

So that’s the start. We always want to find evidence that something is broken for us to do better. When people come to me with problems, I ask the following questions:

- What evidence do we have?

- How many people have you seen struggle?

- How many people have you talked to?

- What kind of research has been done?

That’s the first step. The next one is what can we do that’s going to be significantly better to cause a switch? Because the incumbent always wins. Just think of this from a cell phone perspective. If I came to you and said that I could come up with a new cell phone that was 10% better than your current one, would you switch? The answer is probably no because the switching costs would be immense.

But if I came up with a new cell phone that was completely redesigned – it was not the multi-touch thing we now take for granted. But maybe it had AI and it had augmented reality and even virtual reality, and could make you 10 times more productive. Early adopters might want to give it a try.

People have studied this switching trigger as something that can be measured as an order of magnitude. So think 2X, 3X, to 10X better. If you can start to craft a value proposition around that, that one gets attention. That opens the door for more testing, then seeing if you can deliver on the value promised.

Tell me about the Customer Forces Canvas.

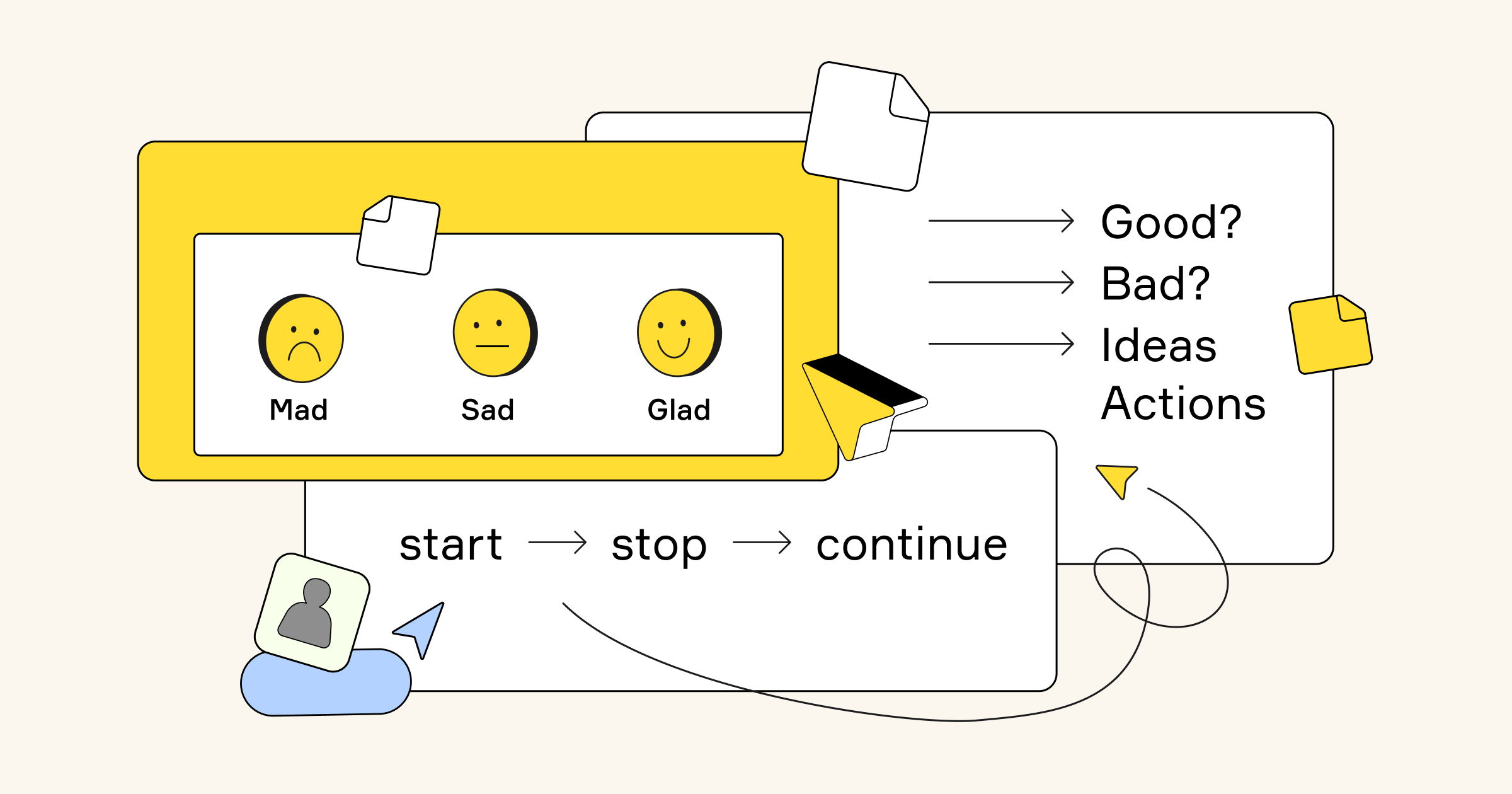

Leaner Canvas is where we talk about what customers and early adopters are doing, what their existing alternatives are, their problems, and what’s broken. Then we take a leap to the unique value proposition, which is what we could promise customers that is three to 10X better.

The Customer Forces is where we begin to understand what’s pushing and pulling people toward this idea of better. How do they define “better?” Is it cheaper? Faster? More convenient? In the Customer Forces Canvas, we get into those levels of measurement.

What are people looking for when you’re stress-testing an idea around inertia and friction in terms of a switch?

The best way to understand why customers buy products is to interview them. And so we want to understand how and in what context they hire certain products. So when they want to pass some time and they’re bored, what are the kinds of things they’re doing? What places are they going? What are they buying? Then what are the forces that get in the way? That’s what we call inertia.

Inertia might be habits that they currently have that they have to break. For example, if somebody wants to get fit, what are things that hold them back? It could be that they don’t have a gym membership or that they haven’t worked out in years. Or they don’t live a very healthy lifestyle. All those are habits that get in the way.

Friction would be behaviors they struggle with as they try something new, like eating healthy or going to the gym. The best products reduce inertia, reduce friction, and have a compelling value proposition. So the ones that pull customers toward this idea of better are the ones that win.

What’s the next validation step?

The best way to really test if people will act is to actually make them act. So the next step I recommend is what we call building an offer. At this step, you put together an offer promising something better. That’s the unique value proposition. So I might talk about my fitness program and how it’s different from the alternatives. Maybe I’ll show a demo. And then we can talk about price. Then I’m looking for a tangible commitment. So are you willing to pre-order? Money exchanged for value or a promise for value is the best validation for an idea.

What do people look for?

One metric that stands out above all is traction. I measure traction in terms of customer engagement. And ideally, that customer is doing something that represents monetizable value.

If that number is going up and all other things hold true, traction goes up. At the end of the day, it’s about identifying one or two key metrics that align with value in the business model, because if we can generate value for customers, getting them to pay becomes a lot easier.

What are some of those derivatives?

If you are trying to sell anything, the first currency of exchange isn’t revenue. It’s attention. The way we do this is by making a promise. You could be walking down the street and see a new restaurant. They have a banner that promises all kinds of pizza or burgers. Something about it grabs your attention. So that’s the first currency.

Then, we go in and there’s an activation moment where we need to make sure that this indeed could meet our promise. That’s the second currency: trust. Do people come to a product and use it for a little while and get value out of it? If that trust manifests, then that leads to ongoing value exchange.

If I go into a burger stand and the burgers smell really good and I get a burger, then I’d be expected to pay. And I happily do that. When I leave, the final currency comes into play, which is referral. or word of mouth. If you generate a happy customer, they typically want to share that happiness with other people. And that’s a very powerful currency.